With just one day to go before the Paris 2024 opening ceremony, I have just come up with a new Olympic Event. I know - my timing sucks.

It’s a combination of the 4x100m relay, and the long jump. Stay with me...

Imagine the scene – the runner, baton-in-hand nears the end of the 400m lap, but rather than passing it on, she continues sprinting - as far as the long jump landing pit, throws herself into the sand and buries the baton, hurriedly raking over the sand afterwards. Once the sandpit judge is satisfied that it is thoroughly hidden, they raise a green flag. Next runner is free to go! She rushes to the long jump pit and launches into a frenetic search to find the baton, before running back to the track, completing a lap, and returning to the sand to bury the baton – and on we go.

What do you think? Could it catch on?

Strange then, how this kind of reflects the default approach to how we share and transfer knowledge. Carefully concealed in a SharePoint sandpit – when perhaps a more personal, relational approach would have been better and just more natural? A Peer Assist or ‘baton-passing’ approach for project handover might be a more effective action.

In a real-life baton pass, think about the careful and deliberate matching of pace, the hand stretching backwards requesting the baton, the holder carefully placing it in the receiver’s hand - have they got it now? – have they *really* got it? - a critical split-second when both are holding the baton simultaneously - and they're off. Now the giver can slow down knowing that nothing was dropped in the process.

Now of course sometimes, the next member of the knowledge relay team isn’t on the track yet – so putting the baton somewhere safe, discoverable and easy to grasp is the best we can do... But let’s try not to rush too quickly to the sandpit though – knowledge management is a team sport after all.

And nobody really likes getting sand in their shoes.

Measuring Knowledge Effectivenes

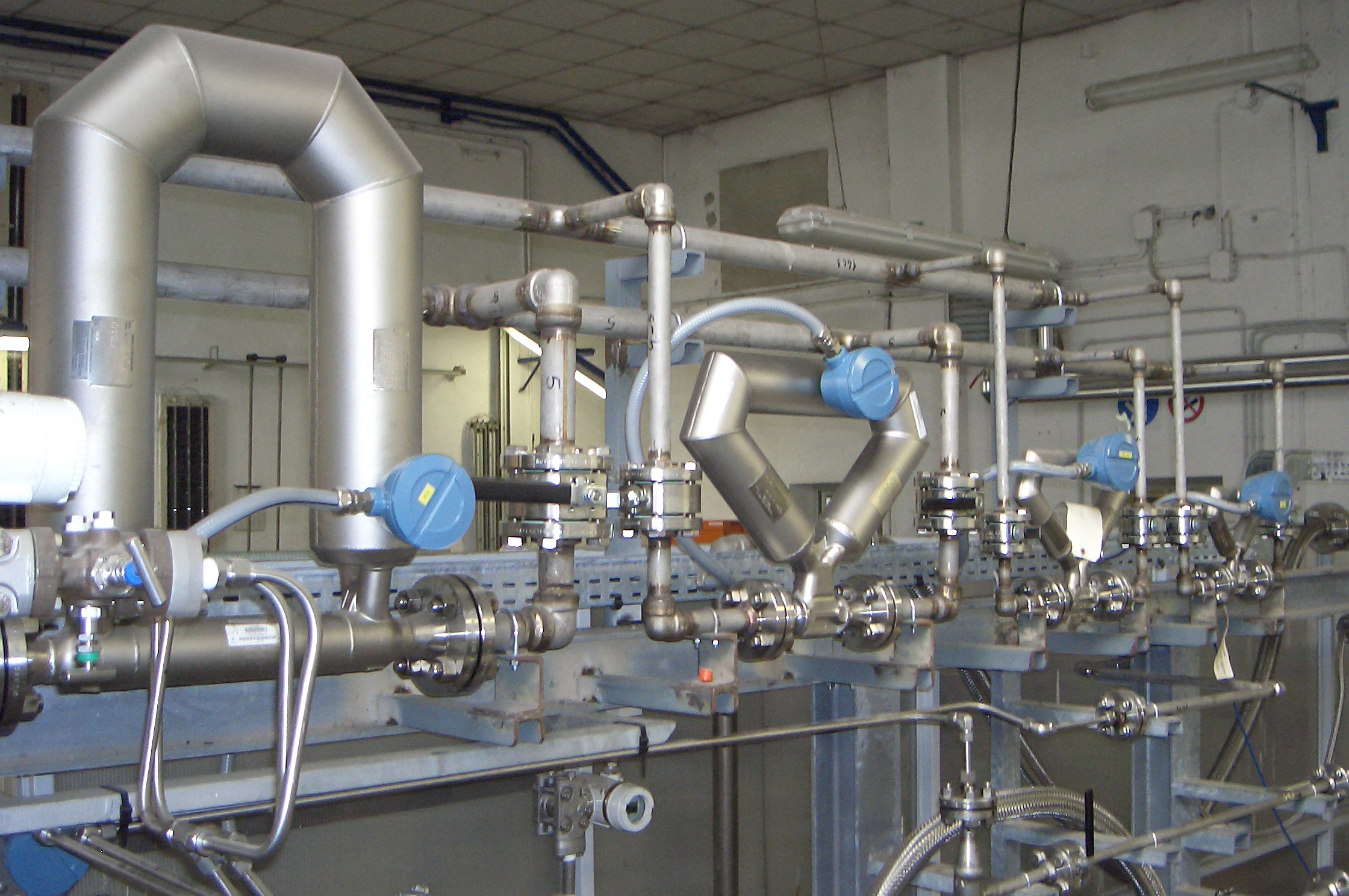

A couple of weeks ago I spent a day with a Chemical manufacturing company, working with their business improvement (BI) community, 50 miles south of Milan. The welcome was very warm, but the fog was dense and cold as we donned hard hats and safety shoes for a tour of the site.

One of the key measures which the BI specialists monitor is that of Overall Equipment Effectiveness – which is defined as:

OEE = Availability x Performance x Quality.

Availability relates to production losses due to downtime; Performance relates to the production time relative to the planned cycle time, and Quality relates to the number of defects in the final product.

It set me thinking about what a measure of Overall Knowledge Effectiveness for a specific topic might look like?

How do we measure the availability of knowledge? Is that about access to information, or people’s availability for a conversation?

What about knowledge performance? Hmmm. This is where a linear industrial model for operational performance and cycle times begins to jar against the non-linear world of sharing, learning, adapting, testing, innovating...

And knowledge quality? How do we measure that? It is about the relevance? The degree to which supply satisfies demand? The way the knowledge is presented to maximise re-use? The opportunity to loop-back and refine the question with someone in real-time to get deeper into the issue?

Modelling how people develop and use knowledge is so much more complicated than manufacturing processes. Knowledge isn't as readily managed as equipment!

If we limit ourselves to the “known” and “knowable” side of the Cynefin framework – the domains of “best practice” and “good practice” - are there some sensible variables which influence overall knowledge effectiveness for a specific topic or theme?

So how about:

Overall Knowledge Effectiveness = Currency x Depth x Availability x Usability x Personality

Currency: How regularly the knowledge and any associated content is refreshed and verified as accurate and relevant.

Depth: Does it leave me with unanswered questions and frustration, or can I find my way quickly to detail and examples, templates, case studies, videos etc.?

Availability: How many barriers stand between me and immediate access to the knowledge I need. If it’s written down, than these could be security/access barriers; if it’s still embodied in a person, then it’s about how easily I can interact with them.

Usability: How well has this been packaged and structured to ensure that it’s easy to navigate, discover and make sense of the key messages. We’ve all read lessons learned reports which are almost impossible to draw anything meaningful from because it’s impossible to separate the signal from the noise.

Personality: I started with “Humanness”, but that feels like a clumsy term. I like the idea that knowledge is most effective when it has vitality and personality. So this is a measure of how quickly can I get to the person, or people with expertise and experience in this area in order to have a conversation. To what extent are they signposted from the content and involved in its renewal and currency (above)

Pausees for thought.

Hmmm. It still feels a bit like an "if you build it they will come" supply model. Of course people still need to provide the demand - to be willing and motivated to overcome not-invented-here and various other behavioural syndromes and barriers, apply the knowledge and implement any changes.

Perhaps what I've been exploring is really "knowledge supply effectiveness" there's a "knowledge demand effectiveness" equation which needs to be balanced with this one?

Hence: Overall Knowledge Effectiveness is maximised when

(Knowledge Supply Effectiveness) / (Knowledge Demand Effectiveness) = 1

Not sure whether the fog is lifting or not. More thinking to be done...

Knowledge, Reciprocity and Billy Ray Harris

Have you heard the story of Billy Ray Harris? It's a heart-warming one.

Billy Ray is a homeless Kansas man who received an unexpected donation when passer-by Sarah Darling accidentally put her engagement ring into his collecting cup. Despite being offered $4000 for the ring by a jeweller, he kept the ring, and returned it to her when, panic-stricken, she came back the following day. Sarah gave him all the cash she had in her purse as a reward, and as they told their good-luck story to friends - who then told their friends - her finance decided to put up a website to collect donations for Billy Ray. So far, $151,000 have been donated as the story has gone viral around the world. Billy Ray plans to use the money to move to Houston to be near his family. You can see the whole story here.

On closer inspection, it turns out that this wasn't the first ring that Billy had returned to its owner. A few years previously, he found a Super Bowl ring belonging to a football player and walked to the his hotel to return it. The football player rewarded him financially, and gave him three nights at that luxury hotel. So the pattern was already established for Billy Ray, who also attributes it to his upbringing as the grandson of a reverend.

Whether you see this story as an illustration of grace, karma or good-old-fashioned human nature, it illustrates the principle of reciprocity.

Reciprocity is an important principle for knowledge management, and one which underpins the idea of Offers and Requests.

Offers and Requests was a simple approach, introduced to make it easier for Operations Engineers at BP to ask for help, and to share good practice with their peers. The idea was for each business unit to self-assess their level of operational excellence using a maturity model, and identify their relative strengths and weaknesses. In order to overcome barriers like "tall poppy syndrome", or a reluctance to ask for help ("real men don't ask directions"), a process was put in place whereby every business unit would be asked to offer three areas which they felt proud of, and three areas which they wanted help with. The resulting marketplace for matching offers and requests was successful because:

i) The principle of offering a strength at the same time as requesting help was non-threatening and reciprocal - it was implicitly fair.

ii) The fact that every business unit was making their offers and requests at the same time meant that it felt like a balanced and safe process.

Like Billy Ray, one positive experience of giving and receiving led to another, and ultimately to a Operations community. A community website for offers and requests underpinned the process, enabling social connections and discussions.

This is played out in the Kansas story, where the addition of technology and social connections created disproportionate value - currently $151,000 of it.

In the words of Billy Ray, "What is the world coming to when a person returns something that doesn't belong to him and all this happens?"

Giving Opinion and Sharing Experience

Last week I spent a day in The Hague, delivering a KM training programme to a group there.As part of the day, after an experiential exercise adapted from the Marshmallow Challenge (which was great fun!), we had a more detailed discussion about the Peer Assist technique.

A Peer Assist, as Geoff Parcell and I said in “Learning to Fly” is

...a meeting or workshop where people are invited from other organisations and groups to share their experience, insights and knowledge with a team who have requested some help early on in a piece of work.

Whenever I teach how this works in practice, I always emphasize that the invitees to a Peer Assist are there to share their experience, rather than give their opinions. Experience, you see, is a precious commodity, an earned reward because someone was present, involved and personally learned from an event – and hence can share their story first hand.

Opinion is cheaper and easier to come by. I can google for opinions; I can give/receive opinion in a LinkedIn group; I can email you my opinion. I can receive opinions on a blog posting or a tweet. Sometimes the opinion given is rooted in experience, but not necessarily. It’s often “retweeted” opinion, amplified from someone else. This video where members of the public give their opinion on the new iPhone (or so they think!), is a classic example of retweeted opinion - the unwitting stars of the show have absorbed so much of the iPhone 5 hype that their received opinions distort their personal experience!

The language we use around Opinion and Experience is interesting.

"Do you want my opinion on that? Let me tell you what I think…. "

Opinion is something which is given. It’s transactional.

It’s like me buying a coke from a vending machine.

In contrast, we would never say “Let me give you my experience”!

We usually ask “Can I share my experience with you?”

As you share your experience with me, I begin to enter your world. I can feel how you felt, see what you saw, think what you thought, and then ask about what I don’t understand.

Sharing experience isn’t transactional – it's a conversation. It’s relational. It’s like we are sharing a meal together.

Why is this important? We have seen a dramatic rise in the number of social channels which surface opinion - within and beyond the boundaries of our organizations. For people like us, who work with knowledge, this is a good thing. We need to put that opinion to work and make sense of the patterns and sentiment available to us.

But all that experience is also still available for sharing....

This post is a plea for us to remain ambidextrous – let’s continue to be smart at working with opinion, and let’s also strategic about learning from experience.

As we immerse ourselves in transactional tide of opinion, let’s make sure that we can still see the richer, personal knowledge available through the sharing of experience. We need to spot the relational opportunities as well as the transactional ones.

Take a closer look at the bottom of that coke machine, and you’ll see what I mean. It's the real thing.

Curiosity has landed - but is it alive and well in our organisations?

Well, hats off to NASA and their partners for pulling off an amazing feat of project planning, innovation, technological wizardry and collaboration. That MARDI video was quite something. Curiosity has landed – let’s see what it finds.

I’ve been reflecting on the topic of curiosity recently, and in fact it even made it onto the cover of my most recent brochure!

Well, hats off to NASA and their partners for pulling off an amazing feat of project planning, innovation, technological wizardry and collaboration. That MARDI video was quite something. Curiosity has landed – let’s see what it finds.

I’ve been reflecting on the topic of curiosity recently, and in fact it even made it onto the cover of my most recent brochure!

In many respects, it is curiosity which closes the learning loop. We can invest vast amounts of effort in learning, reviewing and capturing (when we don’t have an immediate customer to transfer newly generated knowledge to) – but if nobody is curious enough to want to learn from the experience of others, then there is no demand - and no marketplace for knowledge exchange.

That’s why Thomas Friedman wrote about the importance of the “Curiosity Quotient”, created the equation: CQ + PQ > IQ (PQ is Passion Quotient) and wrote:

“I have concluded that in a flat world, IQ- Intelligence Quotient – still matters, but CQ and PQ – Curioity Quotient and Passion Quotient – matter even more. I live by the equation CQ+PQ>IQ. Give me a kid with a passion to learn and a curiosity to discover and I will take him or her over a less passionate kid with a high IQ every day of the week.”

As we look to make our organisations more effective in their use of knowledge, let's keep one eye on how we can increase the levels of curiosity. We can do this through any number of means: leadership encouragement and open questions, raising the levels of awareness of projects and activities, curation, gaming, social serendipity, thinking out loud, peer challenge and peer assistance, overcoming "not-invented-here" and making our organisations a safe place to ask for (and receive) help.

If we could accomplish more of this, then who knows what new life we might discover in KM?

Taking Knowledge for a walk

My shaggy-dog story.In April we had a new addition to the family. Alfie the Labradoodle came into our lives, and for 98% of the time, we haven’t looked back.

You can put that 2% down to unscheduled early mornings, a chewed laptop power supply, a hole in the garden – and a very disturbing barefoot encounter on the lawn after dark. I’ll leave that to your imagination.

The thing I find most remarkable about being a dog owner is that it’s as though you suddenly become visible to people. I have had more conversations with complete strangers in the last three months than in all the 10 years we have lived here. For the first time in my life, random women approach me with a “hello gorgeous” (OK, not me exactly), parents stop me and ask if their toddlers can stroke him, car drivers stop and ask what breed he is and grown men share their innermost ideas about dog training tips and anti-pull harness choices.

It was a bit disconcerting at first, but it’s actually quite pleasant. Perhaps this new social norm is what it was like in the 60’s?

So why so people feel OK to engage in conversation, share their experience and impart wisdom in ways that they never would have done before?

We’ll, it’s obvious I guess – because the dog is obvious. Everyone can see that I’m a dog owner, so my membership of the dog-lovers’-club is visible to all, at the end of a lead. That gives permission for other club members to approach me and ask or share.

This reminds me of Etienne Wenger’s famous definition of Communities of Practice

A group of people who share a concern or passion for something they do, and they learn to do it better as they interact regularly.

You can see where this is going. How much more effective and productive would our organizations be if we made our expertise, our experience, our concerns and our passion more visible to our colleagues? Here are six to consider.

- I’ve written before about the poster culture in Syngenta and how they make their projects and programmes more visible.

- Expertise directories, personal profiles and smart social media which suggests connections generates a culture of greater disclosure are also helpful.

- Retreats where you have time, space and informality to get to know your colleagues better are a natural way to make new connections and deepen existing ones.

- Communities of practice can create a safe place for shrinking violets to flourish, and communities of interest (I’ve seen photography, cycling, food and wine societies, women’s networks etc. in organisations) can also generate the conditions to mix business with pleasure.

- Finally, Knowledge fairs and offers-and-requests marketplaces create a pause – a moment to browse and discover.

So much better than leaving your knowledge in its kennel...

Measuring Knowledge Effectiveness

A couple of weeks ago I spent a day with a Chemical manufacturing company, working with their business improvement (BI) community, 50 miles south of Milan. The welcome was very warm, but the fog was dense and cold as we donned hard hats and safety shoes for a tour of the site.

A couple of weeks ago I spent a day with a Chemical manufacturing company, working with their business improvement (BI) community, 50 miles south of Milan. The welcome was very warm, but the fog was dense and cold as we donned hard hats and safety shoes for a tour of the site.

One of the key measures which the BI specialists monitor is that of Overall Equipment Effectiveness – which is defined as:

OEE = Availability x Performance x Quality.

Availability relates to production losses due to downtime; Performance relates to the production time relative to the planned cycle time, and Quality relates to the number of defects in the final product.

It set me thinking about what a measure of Overall Knowledge Effectiveness for a specific topic might look like?

How do we measure the availability of knowledge? Is that about access to information, or people’s availability for a conversation?

What about knowledge performance? Hmmm. This is where a linear industrial model for operational performance and cycle times begins to jar against the non-linear world of sharing, learning, adapting, testing, innovating...

And knowledge quality? How do we measure that? It is about the relevance? The degree to which supply satisfies demand? The way the knowledge is presented to maximise re-use? The opportunity to loop-back and refine the question with someone in real-time to get deeper into the issue?

Modelling how people develop and use knowledge is so much more complicated than manufacturing processes. Knowledge isn't as readily managed as equipment!

If we limit ourselves to the “known” and “knowable” side of the Cynefin framework – the domains of “best practice” and “good practice” - are there some sensible variables which influence overall knowledge effectiveness for a specific topic or theme?

So how about:

Overall Knowledge Effectiveness = Currency x Depth x Availability x Usability x Personality

Currency: How regularly the knowledge and any associated content is refreshed and verified as accurate and relevant.

Depth: Does it leave me with unanswered questions and frustration, or can I find my way quickly to detail and examples, templates, case studies, videos etc.?

Availability: How many barriers stand between me and immediate access to the knowledge I need. If it’s written down, than these could be security/access barriers; if it’s still embodied in a person, then it’s about how easily I can interact with them.

Usability: How well has this been packaged and structured to ensure that it’s easy to navigate, discover and make sense of the key messages. We’ve all read lessons learned reports which are almost impossible to draw anything meaningful from because it’s impossible to separate the signal from the noise.

Personality: I started with “Humanness”, but that feels like a clumsy term. I like the idea that knowledge is most effective when it has vitality and personality. So this is a measure of how quickly can I get to the person, or people with expertise and experience in this area in order to have a conversation. To what extent are they signposted from the content and involved in its renewal and currency (above)

Pauses for thought.

Hmmm. It still feels a bit like an "if you build it they will come" supply model. Of course people still need to provide the demand - to be willing and motivated to overcome not-invented-here and various other behavioural syndromes and barriers, apply the knowledge and implement any changes.

Perhaps what I've been exploring is really "knowledge supply effectiveness" there's a "knowledge demand effectiveness" equation which needs to be balanced with this one?

Hence: Overall Knowledge Effectiveness is maximised when

(Knowledge Supply Effectiveness) / (Knowlege Demand Effectiveness) = 1

Not sure whether the fog is lifting or not. More thinking to be done...

Knowledge Management and the Divided Brain

Geoff Parcell pointed me in the direction of this brilliant RSA Animate video, featuring renowned psychiatrist and writer Iain McGilchrist. There is so much in this 11 minutes that you'll want to watch it two or three times to take it in, and a fourth, with the pause button to appreciate all of the humour in the artwork. Just superb. Do watch it. [youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dFs9WO2B8uI]

It got me thinking again about parallels between how the brain manages knowledge and how organisations manage knowledge. Ian debunks a lot of myths about the separate functions of left and right hemispheres and emphasizes the fact that for either imagination or reason, you need to use both in combination.

- Left hemisphere - narrow, sharply focused attention to detail, depth, isolated, abstract, symbolic, self-consistent

- Right hemisphere - sustained, broad, open, vigilant, alertness, changing, evolving, interconnected, implicit, incarnate.

We share some (but not all) of these left/right distinctions with animals. However, as humans, we uniquely have frontal lobes.

- Frontal lobes - to stand back in time and space from the immediacy of experience (empathy and reflection)

I think a holistic approach to knowledge management which mirrors the brain will pay attention to breadth, depth, living connections and reflection. This has implications for the way we structure and navigate codified knowledge - moving between context and detail, abstract to interconnected - and also reinforces the relationship between KM and organisational learning (the frontal lobe bit).

I believe that an effective knowledge management strategy will creatively combine each of these components in a way which is balanced to the current and future needs of the business.

In a way, a lot of first generation KM was left-brain oriented. Second and third generation KM have combined the learning elements of the frontal lobes with the living, inteconnected right brain. That doesn't mean that first generation KM is no longer relevant - I would assert that the power is in the combination of all three - see this earlier posting on KM, Scientology and Top Trumps!

It's probably the last minute which is the most challenging. Does your KM strategy, led self-consistently by the left hemisphere, imprison your organisation in a hall of mirrors where it reflects back into more of what it knows about what it knows about what it knows?

The animation closes with Einstein's brilliantly prescient statement:

"The intuitive mind is a sacred gift. The rational mind is a faithful servant. We live in a society which honours the servant, but has forgotten the gift."

Smart man, that Einstein chap.

How children share - Davenport's Kindergarten Rationale

I've always believed that we can learn a lot from children as analogues for behaviours in organisations. They're just like us, but usually more transparent about the motives for their actions.

A few years ago, I was asked to present at an internal conference for a large Oil Company and had the opportunity to put that to the test. Tom Davenport, co-author of Working Knowledge once shared his "Kindergarten Rationale" for why children share:

You share with the friends you trust

You share when you’re sure you’ll get something in return

Your toys are more special than anyone else’s

You share when the teacher tells you to, until she turns her back

When toys are scarce, there’s less sharing

Once yours get taken, you never share again

With the help of the of the local team (and the permission of the parents!), we video-interviewed several of the children of the leadership team, asking them questions like "What makes you want to share?" and "What kind of children do you like to share with?".

You can imagine the impact that these vignettes had when played back to the 200-strong audience, who delighted in spotting which children belonged to which leader, and particularly enjoyed the moment when the 6 year-old son of the Finance Chief said that he only liked sharing with people who gave him something just as nice in return...

Perhaps we should ask our children some other interesting knowledge management questions:

How do you come up with new ideas?

What stops you asking for help?

What kind of people make group-work easy?

Why do you make the same mistakes more than once?

Wise words might be closer (and cheaper) than we think.

Speed Consulting

Have you ever wondered what it would be like if you combined speed dating and knowledge-sharing? I can’t own up to any firsthand experience of the former, but I’m told by friends who do, that you participate in a merry-go-round of three-minute exchanges on a room full of tables-for-two. When the bell rings you move around to the next person. If you like what you’re experienced, you make a note on your score-card, and, if the feeling was mutual, you take the next steps together. Tremendously efficient and less emotionally risky than the traditional approach - at least for most people!

To save a praying mantis experience, there are websites full of interesting questions that you might ask during your 3 minutes – for example: “What luxury item would you take on a desert island?” and “What are your favourite words and why?”. Incidentally, “knowledge management” is not a good answer to the second question. So if speed-dating is designed to reduce the emotional investment, embarrassment and risk of failure of finding a potential partner – what can we learn from that room-full of tables which we could apply in a KM context?

In my work with communities of practice and networks over the years, I have observed that when someone asks a question in a network, people are sometimes reluctant to offer up suggestions and ideas because they don’t have a complete answer or a polished response. The longer the silence lasts, the more risky it feels to contribute. People hold back, worried that they might be the only one to respond and that their idea will be perceived as being too trivial or too obvious – how embarrassing! If your community feels like this, and you have an opportunity to meet face-to-face, then let me recommend a simple “Speed Consulting” exercise which can help groups to break these bad habits. (I’m indebted to my friend and consulting colleague Elizabeth Lank for introducing me to this technique).

A quick guide to speed consulting.

Identify some business issue owners In advance, identify a number of people (around 10% of the total) with a business challenge which they would like help with – they are to play the role of the client who will be visited by a team of brilliant management consultants. Business issues should not be highly complex; ideally, each issue could be described in 3 minutes or less. Brief the issue owners privately coach on their body language, active listening, acknowledgement of input etc. Remind them that if they are seen to have stopped taking notes (even when a suggestion has been noted before); they may stem the flow of ideas.

Arrange the room You need multiple small consultant teams working in parallel, close enough to generate a “buzz” from the room to keep the overall energy high. Round tables or chair circles work well. Sit one issue owner at each table. Everybody else at the table plays the role of a consultant. The issue owner will remain at the table throughout the exercise, whilst the groups of “visiting consultants” move around.

Set the contextExplain to the room that each table has a business issue, and a team of consultants. The consultants have a tremendous amount to offer collectively – from their experience and knowledge - but that they need to do it very quickly because they are paid by the minute! They have 15 minutes with each client before a bell sounds, and they move on to their next assignment. The time pressure is designed to prevent any one person monopolising the time with detailed explanation of a particular technique. Instead, they should refer the issue owner to somewhere (or someone) where they can get further information. Short inputs make it easier for less confident contributors to participate.

Start the first round Reiterate that you will keep rigidly to time, and that the consultants should work fast to ensure that everyone has shared everything that they have to offer. After 15 minutes, sound the bell and synchronise the movement to avoid a “consultant pile-up”.

Repeat the process Issue owners need to behave as though this is the first group and not respond with ‘the other group thought of that!’. They may need to conceal their notes. Check the energy levels at the tables after 45 minutes. More than three rounds can be tiring for the issue owners, but if the motivation is particularly high, you might manage 4 rotations.

Ask for feedback and reflection on the process Emphasise that the issue owners are not being asked to “judge” the quality of the consultants! Invariably, someone will say that they were surprised at the breadth of ideas, and that they received valuable input from unexpected places. Ask members of the “consulting teams” to do the same. Often they will voice their surprise at how sharing an incomplete idea or a contact was well received, and how they found it easy to build on the ideas of others.

Transfer these behaviours into community life Challenge them to offer up partial solutions, ideas and suggestions when a business issue arises in a community. Having established the habit face-to-face, it should be far easier to continue in a virtual environment. The immediacy and brevity of social media helps here – perhaps the 140 character limit in Twitter empowers people to contribute?

So perhaps I should have just tweeted: @ikmagazine http://bit.ly/speed_consulting boosts sharing in communities #KM @elank and waited to see what my followers would respond with! To be published in the next edition of Inside Knowledge.